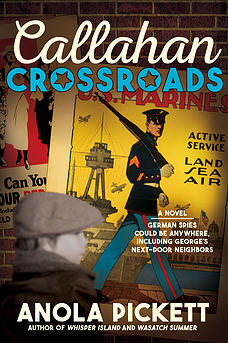

Artist Elaine Duncan Tends Fire Damaged Paintings

Part One

MIRACLE ON DEPOT STREET:

ELAINE DUNCAN’S ARTWORKS SURVIVE BLAZE

Sometime before 7:19 p.m. on Wednesday, November 16, 2011, fire broke out in Fairfield at 406 W. Depot Avenue. Built in 1919, the burning two-story structure contained apartments, businesses, and art studios. At first, the fire progressed slowly, allowing all the building’s residents and their pets to safely escape.

During this early, optimistic stage, Fairfield artist Elaine Duncan received a phone call from a friend who knew she maintained a studio on the burning building’s second floor. For eight years, this studio had housed all her art supplies, tools, and over 700 of her drawings and paintings.

“At the time there was hope the firemen would put the fire out and my studio would only suffer smoke damage,” Elaine reported later in emails to friends. “I went to sleep with images of cleaning everything and dragging it over to my basement. That is, if anything survived. I knew this was only one possibility,” she added.

While Elaine slept, 60 firemen from Fairfield and nearby communities battled the blaze, but the situation worsened. Explosions in a woodworker’s shop in the building’s southeast corner forced firefighters to evacuate and fight the fire from outside.

Early Thursday morning Elaine drove to West Depot Avenue. Yellow tape cordoned off the block. Small fires burned, and smoke billowed from rubble inside the building. Elaine could clearly see the smoldering rubble because the building’s roof had collapsed.

“The top floor was gone,” she reported. “That is where my studio had been.”

No one could yet enter what remained of the structure, so Elaine left to meditate and begin emotionally processing her losses, which weren’t covered by insurance. Sadness over losing a particular painting or tool vied with relief over not having to undertake an arduous restoration effort.

“My work got a first class cremation,” she concluded.

But that wasn’t entirely true. On Friday, December 2nd, while two workers cleared debris from the building, one pulled back a thick, wet corner of cardboard and exposed a colorful painting. A partly burned countertop weighed down by chunks of roof had preserved a stack of drenched, 22” x 30” artworks.

“Evidently the firemen blasted my studio space with water just before the countertop caught full fire,” Elaine later explained.

The workers carried the paintings to a cleared corner and covered them with a wheelbarrow. They consulted Martin Brodeur, the building’s owner, who recognized the paintings as Elaine’s.

On Saturday, clutching Martin’s jacket sleeve, Elaine followed him through the dark, debris-filled first floor and up an intact back staircase. On the exposed second floor, coils of wire jumped and rolled in the wind. Ash blew everywhere.

Later, Elaine explained that the second floor “had become a completely open space punctuated by charred roof pillars flame-carved into strange, nondescript totems.”

Martin and Elaine picked their way carefully across the wet, slippery floor to the wheelbarrow.

“Charcoal touched everything and an ash gray skin covered all possible color,” Elaine reported. “Marty lifted back a swath of paintings and revealed my painting Fairy Light. It was pristine. I was amazed.”

Could the soggy paintings be saved? How? Martin advised Elaine to quickly relocate her artwork, but where could she take it? Her small apartment and shared basement space wouldn’t accommodate restoration efforts, she realized. At home, Elaine emailed friends for advice. Help came swiftly.

On Sunday, two strong male volunteers made three precarious trips inside the rubble-filled ruins to retrieve the heavy, water-logged paintings. After loading them into a van, they drove to an old school and carried them down to its basement. Elaine had received permission to use it rent-free for four days as a drying space.

Shortly after the men left, other volunteers carried in towels, sheets, and absorbent paper. They helped Elaine separate the paintings and spread them on the floor. Glassine she’d placed over each painting before storing them in her studio facilitated this three-hour-long process. Like carefully tended garden plants, rows of cheerful paintings alternated with walkways that created easy access for restoration.

Borrowed fans hastened drying, and 24 hours later Elaine began removing surface soot and ash with the help of another friend and his Shop-Vac. Vacuuming took two days. Elaine tallied the paintings as she restacked them for relocation to another donated space. Thanks to 60 firemen, two workers, and countless friends and helpers, Elaine recovered one hundred paintings.

“I am blessed to live in a community of caring, generous people,” she confided.

Arduous work lies ahead. Elaine will garner information and experiment. She’ll erase fine ash and soot, trim paintings, adjust images, and completely transform some artworks. Despite the work involved, she feels undaunted. The miracle of her paintings surviving a disaster that destroyed much sturdier objects enlivens her efforts to save them.

This article appeared in The Iowa Source:

© 2012 Cheryl Fusco Johnson.